Quest for The Cosy

The task was simple: identify what was screening at the Cosy Cinema, Kings Heath during its brief existence in the early C20th and then to choose a silent film suitable for a 2025 audience.

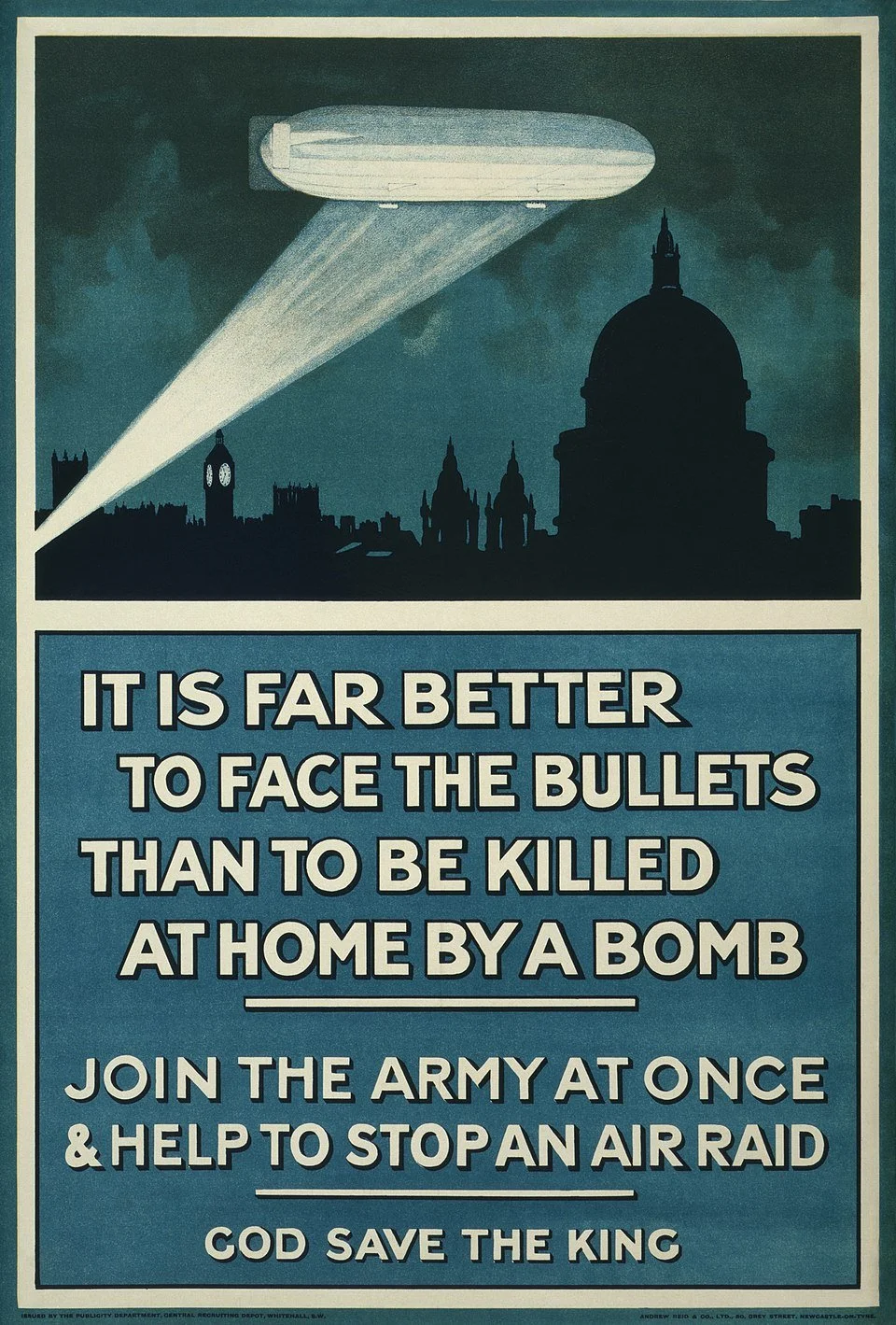

Between 1911 and 1915, a small cinema ran in the space currently occupied by •Nook• Gallery and Studios. It was known as The Cosy in its last few months of operation and was one of many new 'cinematograph halls' screening silent films across Birmingham, accompanied by live, semi-improvised music. The suburban cinemas especially would have looked more like film clubs, repurposing existing meeting halls to screen a continuous, pot-luck programme.

•Nook•'s gallerist Gosia learned from locals that her building used to be a cinema and for the past year or so, •Nook• has paid homage to The Cosy (previously known as the Kings Heath Electric Picture House) with a revived local film club, screening lesser-known documentaries, arthouse and international titles. The various Birmingham cinema history books confirmed the names and dates but were otherwise short on detail. My promise to Gosia and Darren was to provide at least one suitable title and to fill out the Cosy story.

I had conducted similar research for my guided walk Invisible Cinema, which focused on lost or converted cinema buildings. Researching those city centre establishments and their programs involved revisiting archived What's Ons and the various Birmingham newspapers of the day. The story of cinema spans the entire twentieth century, from the silent era screens of The Electric on Station Street and The Picture House New Street, now occupied by Piccadilly Arcade (the slope of the arcade reflects the rake of the auditorium).

However, there was a key difference in how the city centre cinemas operated, compared to those in the suburbs.These were luxury destinations, with plush furnishings, top-quality refreshments, themed decor and high-profile presentations, perhaps at triple entry price of the shady fleapit at the end of your street. The de luxe cinemas advertised their particular, popular titles, while humbler cinemas such as The Cosy simply advertised an all-day 'continuous programme', in the manner of the live variety shows of the Victorian era.

It meant that I found no Cosy Cinema listings during my first flick through the 'amusements' listings of the local press, but I enjoyed the experience of being immersed in the world of whizzing microfilm reels—something cinematic about such old-school research. In the 1990s, I worked in the (now lost) Central Library and learned about Birmingham’s archived holdings and special collections from the requests of the cultural history researchers of the day. Nostalgic analogue research modes aside, by extending the search with the online digital British Newspaper Index, I discovered a single review—of sorts—of two titles taken from The Cosy's 'continuous programme'. No titles at all emerged from the cinema's previous incarnation the Kings Heath Electric Picture House. Other digital resources helped illuminate the picture.

The first rumblings of a cinema at Ruskin Hall, Institute Road began on 28 September 1911 when the Cinematograph & Lantern Weekly reported the registration of King's Heath Electric Pictures Ltd at Somerset House:

This company has just been registered with a capital of £700 in £1 shares, to carry on in King's Heath and elsewhere the business of theatre proprietors, producers of kinematograph, bioscope, and animated picture displays &c

The subscribers are named as RG Stephens of 101 High Street, King's Heath (a space now occupied by ASDA) and Mrs Ellen Allen of 22 Valentine Road, also in King's Heath. A 'kinematograph' is the camera, while a 'bioscope' is the projector, but both distinct machines were named interchangeably to mean 'cinema'. It is interesting to see that the license allowed films to be made as well as screened—entrepreneurs still feeling their way in cinema business during this early period. By April 1912, the Kings Heath Electric Picture House appears in the Places of Recreation and Amusement section of Kelly's Birmingham directory, with AH Allen named as the manager and secretary, along with his noisy neighbours:

Charles Price - builder

Eldred Hallas - furniture remover and coal merchant

Wragg Bros - stone masons

Dickenson &Co - painters

Christadelphian Meeting Room

King’s Heath Mission

A contemporary press advert identifies matinees on Wednesdays and Saturdays that surely must have been met with some audible industrial overspill.

By February 1913, the manager was Harry R Ashford. In January of the following year, the cinema was advertised for sale in the Yorkshire Evening News: 'Birmingham picture palace for disposal, fully equipped, going concern, splendid business, profits around £10 weekly, price £550 or near offer.' On March 25, the Birmingham Dispatch reported:

Picture Palace Purchase - Alleged Fraudulent Misrepresentation - Vendors Sued

Augustus Collins brought an action against Richard Gardner Stephens and Harry Richard Ashford, [who] claimed it was making £3-5 per week but [who had] been falsifying the books, and [the cinema] was running at a loss.

Collins bought the business for £200, but when he found out it was losing money, he offered it back to the defendants for £100, which they did not accept. He managed to sell it for £130. These shenanigans offer some clues to the quick evolution of the cinema economy, the cut-throat nature of the business, as well as the unpredictable appetites and loyalty of audiences. Since February 1913, Kings Heath residents had the added option of the purpose-built 542-seater Ideal Picture House on York Road.

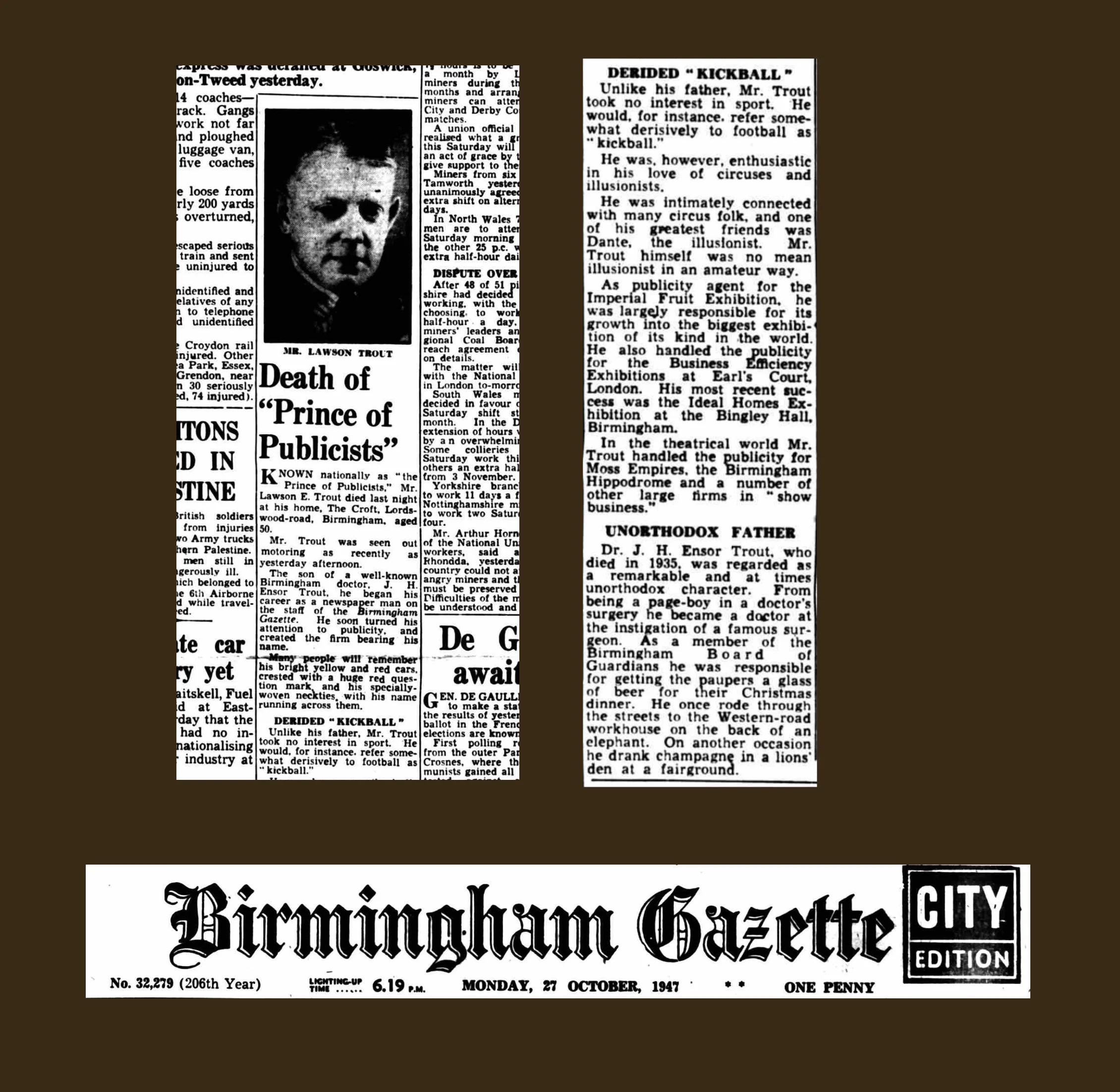

By June 18 1914, the cinema is up for sale again, this time without the promise of any specified likely return but with some specifics about the size for the first time: 'seated for 320, fully equipped, apply Cochrane, Ruskin Hall'. The cinema is next mentioned in the Dec 31, 1914 edition of The Bioscope, now rebranded as The Cosy Cinema. The new manager is named as Lawson Trout in the 1915 edition of Kelly's Birmingham Directory. No further 'for sale' adverts appear after the summer of 1914, suggesting that Trout took over that season for a duration of not quite a year. Despite Trout's youth (he was just 18 years old when he took over the cinema) and short tenancy, he emerges as the brightest star of the Cosy story.

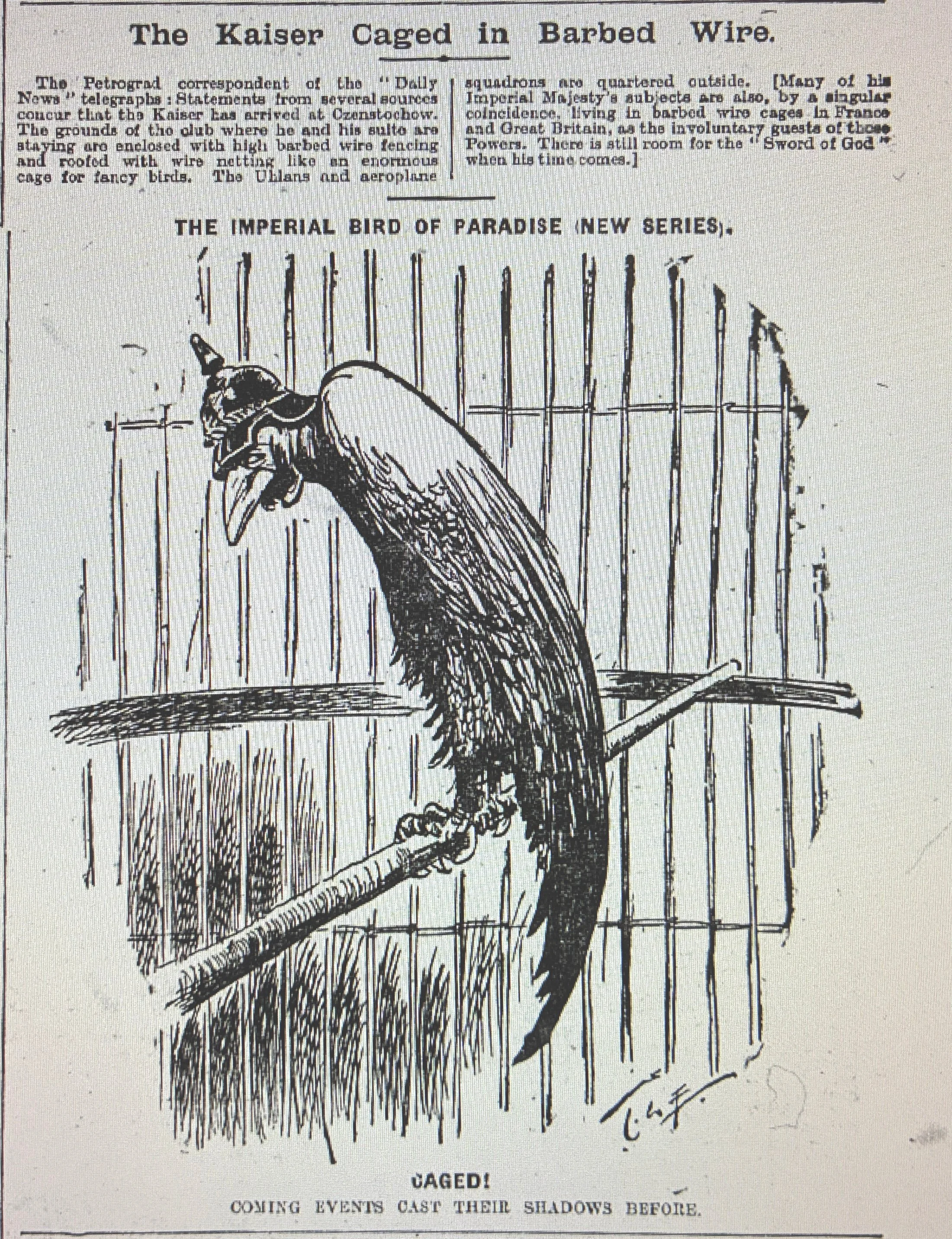

The Bioscope's Christmas round-up of Birmingham screenings visits the Great Hampton Picture Palace, Livery Street, the Balsall Heath Picture House, the Moseley Picture Palace, The Ideal, King's Heath and finally The Cosy Cinema, conveniently following the route of the number 50 tram. By ending at one of the city's smallest and certainly lesser-known cinemas, could the anonymous correspondent have been Trout himself? Certainly he would go on to review cinema for The Kinematograph before establishing himself as one of the city's leading publicists, so this could well have been an early bit of promotion.

The Cosy Cinema wraps up in Spring 1915 in unexplained circumstances. On March 25, 1915, The Kinematograph reports that:

The licensing sessions for the Birmingham kinema theatres have passed off without any sensational happenings, the owners and managers of the majority of the houses against whom notices of objection had been served having cheerfully complied with the requirements of the local authorities.

The theatres which have permanently been refused licenses are the Old Steam Clock, in Moorville Street; the King's Heath Institute; and Ruskin Hall [The Cosy Cinema], Institute Road, King's Heath. The last named, by the way, is to be converted into a billiard hall.

The proximity of two of the city's three theatres being refused licenses is curious (The Institute stood just 100 yards from The Cosy, now occupied by Poundland). Did the managers together resolve a reason not to ‘cheerfully comply’? We may never know, but the official order highlights a previously overlooked detail of Birmingham's early cinema history, namely that The Institute also had equipment for early screenings. The final reference to the cinema comes during 1916, with the building being outlined and labelled on the forensically-detailed Ordnance Survey map, drawn up the previous year. The Cosy story ends here—or rather it takes an extended intermission until •Nook• Gallery reawakens its dormant identity.

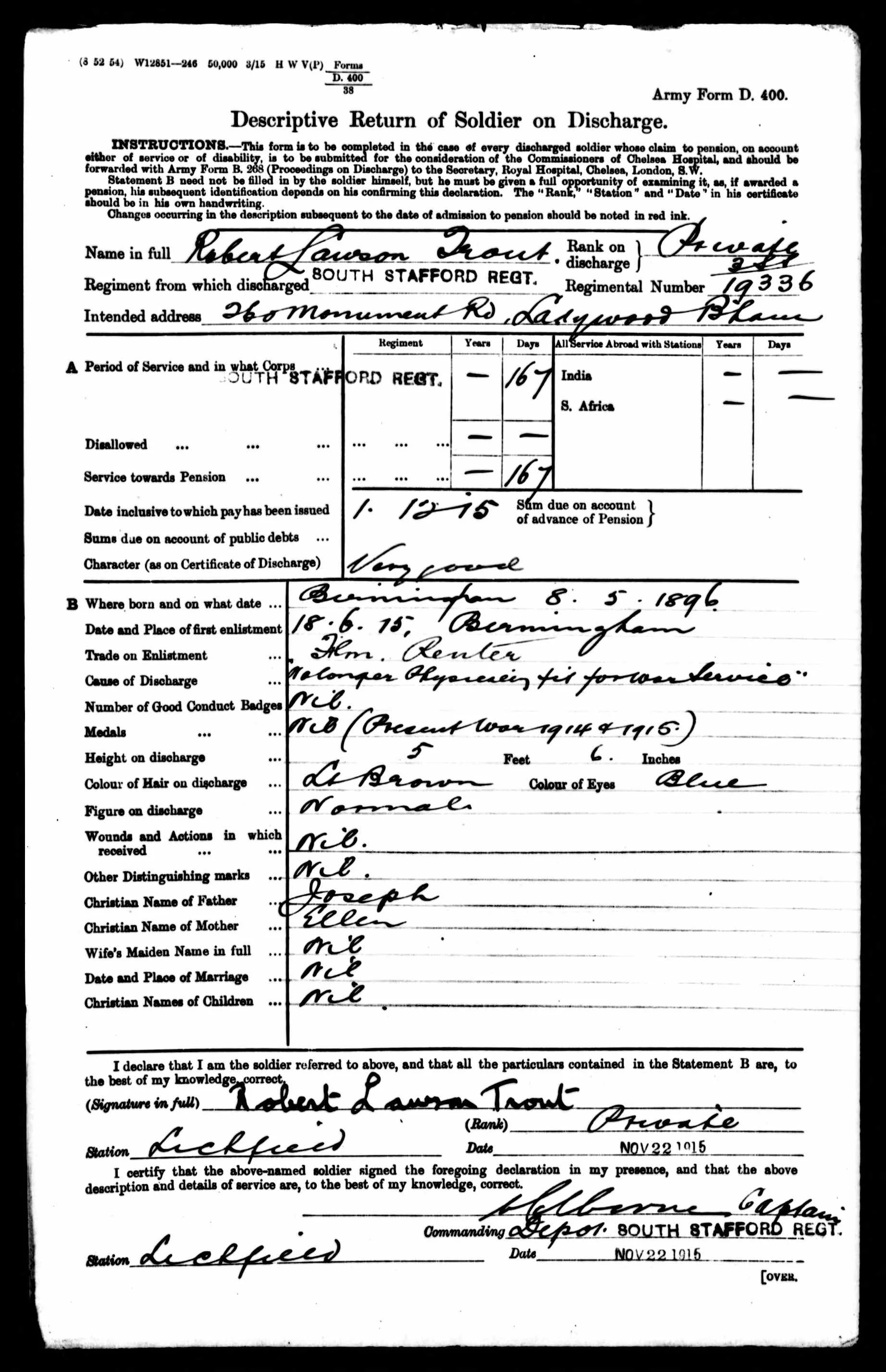

As a professional publicist, Trout's story is easy to trace, with announcements and advertisements regularly appearing in the local and national press. After the closure of The Cosy, he enlisted in the army, serving with the South Staffordshire Regiment between June and November of 1915, and returning without injury. By 1918, he was writing for the Birmingham Gazette and had a regular 'Birmingham Notes' column in The Bioscope—perhaps the unrecorded years 1916 and 1917 were spent qualifying for this new journalistic career. He maintained at least a loose connection with Birmingham cinemas into his later life, with 'situations vacant' adverts appearing into the 1940s for usherettes and stage technicians.

He married twice and had a daughter but died young at the age of 50. His obituary in the Birmingham Dispatch describes him as the 'Prince of Publicists'. 'Many people will remember his bright yellow and red cars, crested with a huge red question mark and his specially-woven neckties, with his name running across them.' The Dispatch reports he was a great lover of circuses and illusionists—and was himself a skilled magician.

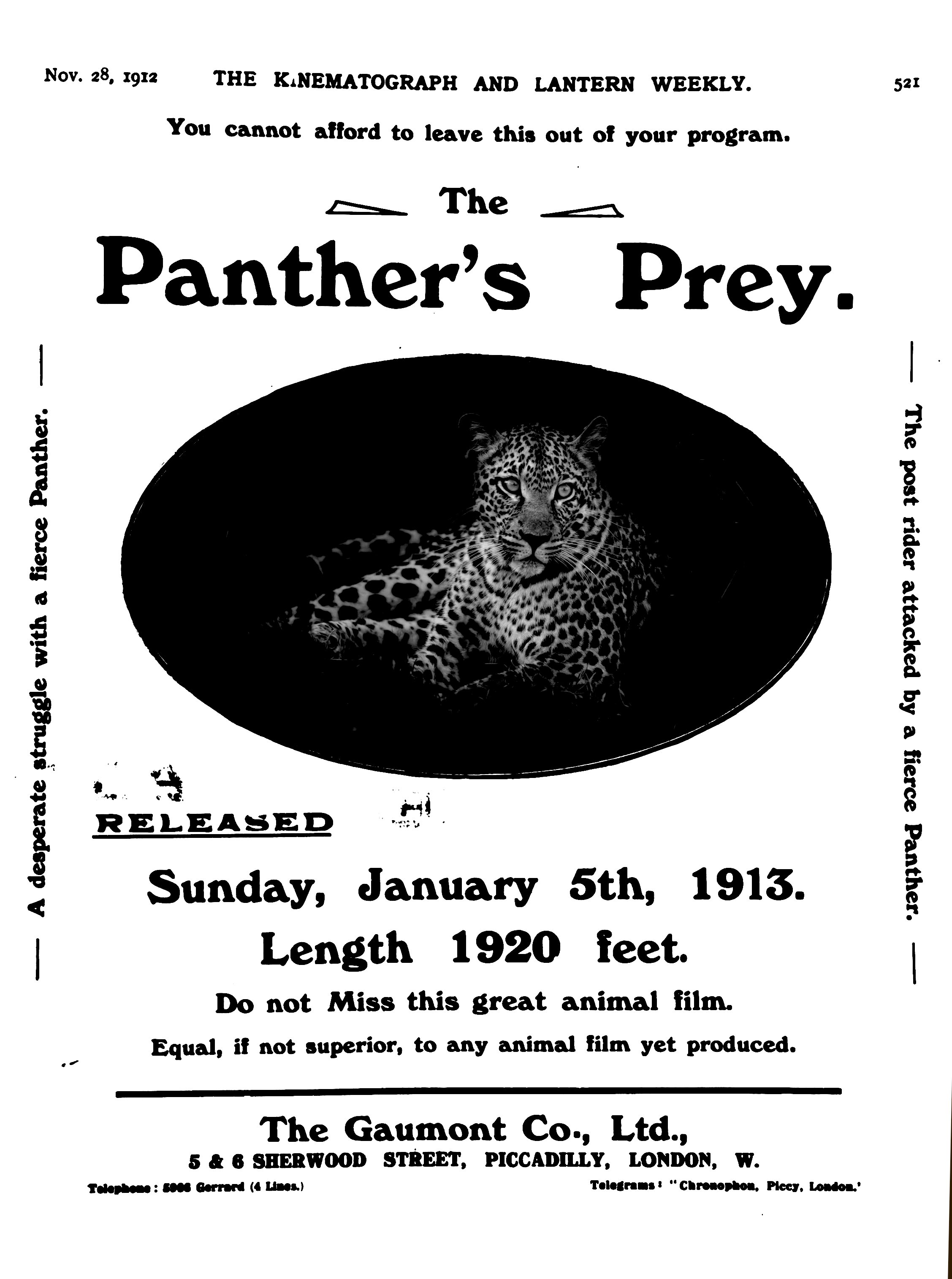

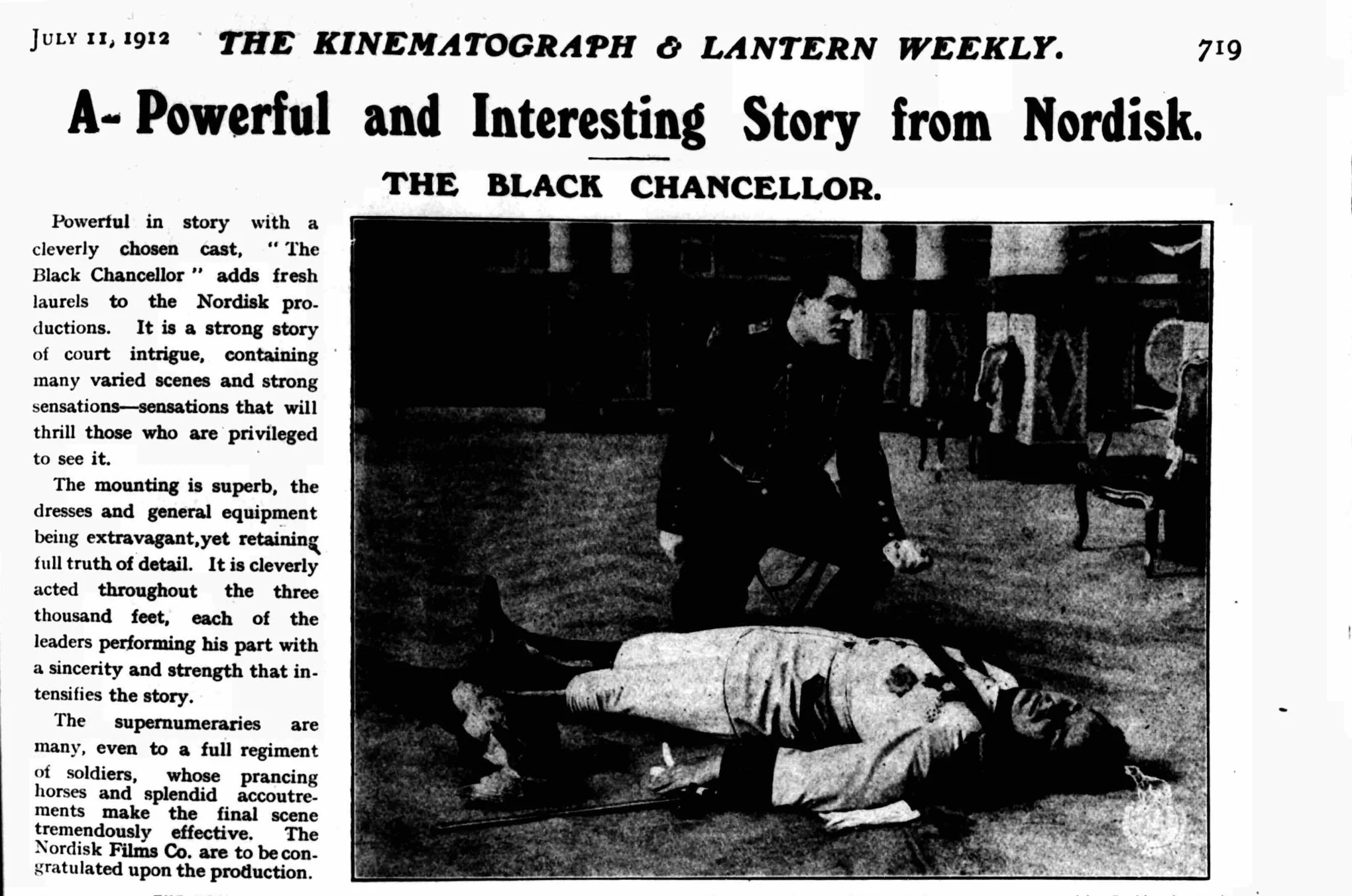

To return to my original curatorial quest, I eventually selected the 1913 historical thriller The Black Chancellor, by virtue of it being the only available title that I could find of only two named films that were listed as showing at either The Cosy of the Kings Heath Electric Picture House. The other title, The Panther's Prey, was 'a 40-minute film including a thrilling attack by a leopard upon imprisoned and unprotected woman,' and appears to be lost. Rather more suitable for community viewing, I felt, was The Black Chancellor. In April 1913, Moving Picture World wrote:

It is a great picture, splendid old world settings of castle moat and mansion, beautiful exteriors of flowering field and smooth highway and excellent direction. The drama runs smoothly.

The film features some furious letter-writing in opulent Bavarian castle interiors; not exactly dramatic but essential for story exposition in a silent setting. The film studio and the actors are Danish, which would not present a language barrier until the days of the ‘talkies’.

How fortunate to find anything to screen at all! Early films were not thought to have value beyond their theatrical run, so many were discarded soon afterward, or otherwise perished. The ratio is sometimes expressed as six ‘ghosts’ to every survivor. If the 1914 Bioscope review was indeed written by Trout, then he himself provided us with the eventual film selection.

To borrow from the The Bioscope's succinct review of 1914, the 2026 screening of The Black Chancellor, exactly 111 years after the first, 'did well'! A full house braved the December bleakness of Institute Road and were further rewarded by a live, semi-improvised soundtrack provided by local musician and artist Russ Sargeant. I introduced the film with some of the above notes and Gosia shared her own research into the film’s lead actor Valdemar Psilander.

The remit of the various digital newspaper indexes are ever-expanding, with more local and national titles being added all the time. Maybe further silent era films shown at The Cosy will be revealed and screened but for the moment you can sign up to •Nook•’s mailing list to keep informed of their contemporary screenings and events.