How I wrote ‘111 Places in Birmingham That You Shouldn’t Miss’

What a thrill to be asked write a guide book about Birmingham, especially as I had never written a book before. My German publishers cautiously enquired: Can Birmingham yield enough material? I reassured them there were plenty of worthwhile destinations that together would tell the Birmingham story, and suit their off-the-beaten-track outlook. Devising a definitive list prompted much internal debate about how readers should experience 'my Birmingham'.

All of the 111 Places… guide books actually feature 222 places, as each chapter includes a bonus nearby tip amongst the main entry’s address and visiting details. These minor aspects of city life sometimes outshine the main feature. Not everything in the book is a place, such as my chapter on folk hero Foka Wolf and gastro-oddities like Orange Chips. The definition of Birmingham is also challenged. My book takes a no-borders stance by straying into the Black Country, Solihull and even Worcestershire. This was done to vary the physical terrain as much as to tell the city's fuller industrial story.

Emon's 111 travel guides are written by city residents who know the places that never make it into guide books. It’s a smart approach—usually professional travel writers have a limited time in which to research and review a previously unfamiliar city and end up recycling the same familiar, highly-marketed locations. These days, most people can produce their own digital city itinerary in seconds, with an algorithm primed to favour shopping and eating destinations with a few proven heritage draws. The 111 Places… books pick up where the Top 40 bots ends their limited search.

I started out by listing 40 Birmingham spots and finishing four chapters that proved my mettle. These were approved, so I spent a month compiling my full 111 list. The whole thing was shot down the same morning I submitted it—too many obscure buildings and a glut of restaurants and bars. The city’s new food scene still felt fresh after decades of Bella Pasta and JD Wetherspoon, but in trying to rebadge Birmingham, instead of presenting its true character, I had repeated a common mistake. I waved goodbye to my Michelin-starred white truffle fettuccine, paired with lesser-known white wines of Italy, and said hello to orange chips and blue pop. And what else?

Birmingham's defining factors are: a deep-rooted car culture, its industry backbone and an unexpected post-war endorsement of modernism. I'd been asked to cut back on buildings, but the city’s mix of sacred spaces was just too architecturally interesting to ignore, so too the city's few Brutalist survivors. Industrial-era features like windmills, tunnels, bridges and quarries required forays into the Black Country…Brum's are gone. I illuminated the city’s strong Italian links and addressed how Birmingham has responded to its lack of natural water features. There's no light without shade and so the book has many demons, spirits and grotesques at play in its pages.

Does Birmingham have a unique and identifying cuisine? Not really. Baltis are essentially quickly-cooked versions of long-existing curry recipes, served in vessels originating elsewhere. Chocolate, custard and other industrialised foodstuffs don't count as cuisine, nor does Mr Egg. Orange chips have more local authenticity than the various delicious pastas, boutique wines and other imported morsels. I also endorse an apple tree growing in a Selly Park street, to represent an optimistic city future of sustainable living. Its fruit is also exceptional.

The guide avoids ‘More Canals Syndrome’, namely the jarring insistence that Venice’s beautiful, ancient waterways don't measure up to Birmingham’s industrial-strength mileage. It's a brute force approach to quantifying cultural worth but Birmingham leads the world in such hyperbole. Claims like ‘Invented the screw’, ‘invented oxygen’, ‘invented tennis’, ‘invented custard’, ‘world’s tallest campanile’, ‘Europe’s biggest park’, ‘more trees than Paris' are dubious but harbour a genuine longing to be celebrate the city's significance, creativity and ingenuity. I recall a souvenir tea towel on sale at tourist information centres—back when those still existed—listing dozens of these unchecked 'everyone-knows' pleas which in some households became an unofficial city manifesto. Instead, my book would be a robust portfolio of true and worthy boasts and revelations.

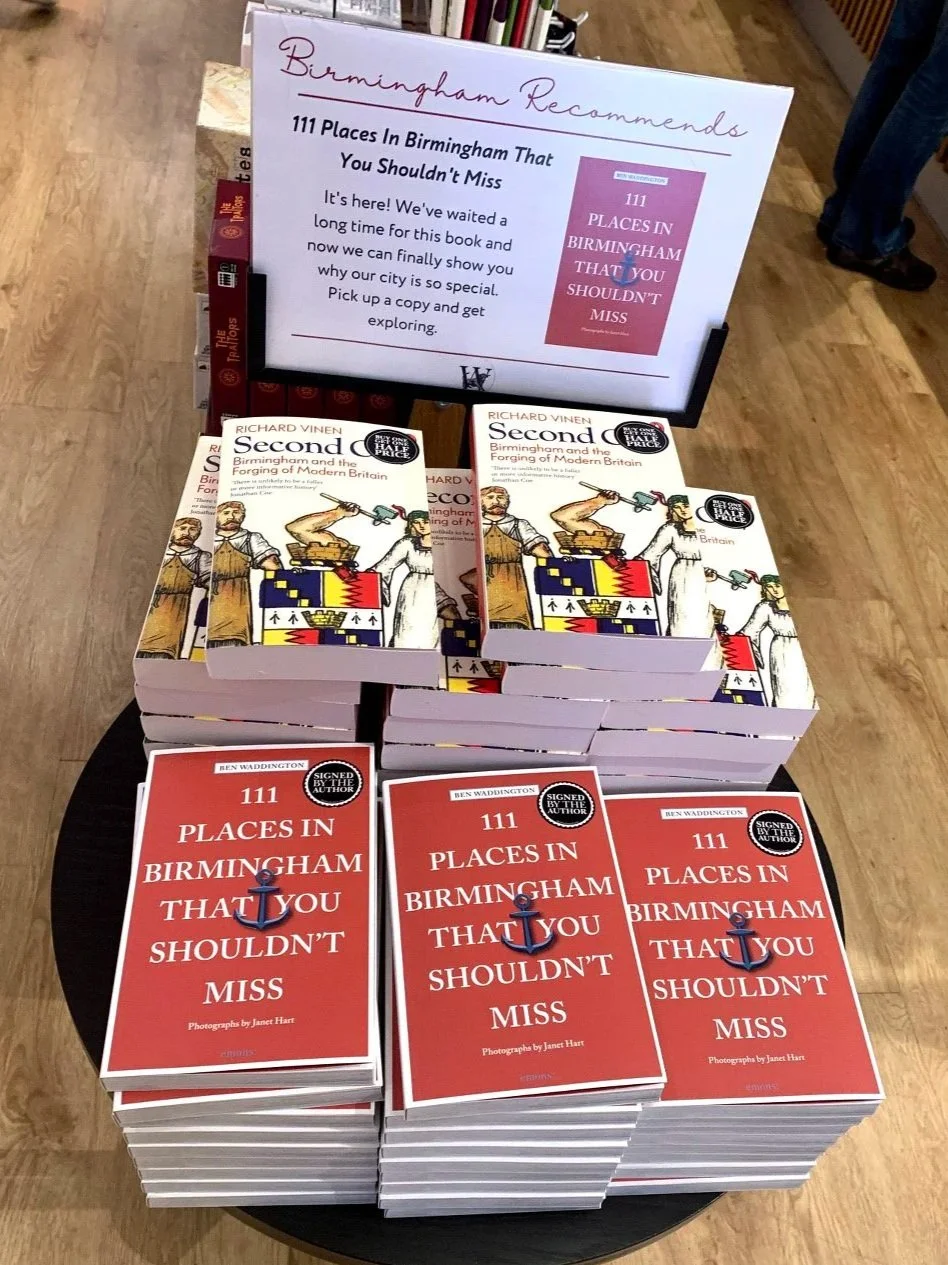

The tinkering paid off and Emons accepted my revised manuscript with only minor changes being made to the finished version which is available in all good bookshops, or which you are going to be given on your next birthday. The book’s photography was a separate story—a nightmarish one with lockdown red tape, chased permissions and delays, that is until Janet Hart took over the project with vigour and imagination. Upon finishing the book, I felt a renewed warmth towards a city that had at times disappointed, squandered opportunities, taken shortcuts, or otherwise neglected itself. All cities have their moments of beauty, intrigue and triumph as well as moments of ugliness, failure and bad design. Each city has its own balance of these elements, with some cities offering endless natural beauty, ancient universities, histories of nobility and integrated cultural economies to make them effortlessly appealing. Birmingham is not such a city; it is one of industrial origins and enterprise, and has developed industrial sensibilities that are still with us, raw and bold. Its quieter moments of achievement, individuality, beauty and transcendence often have to be signposted.

‘Do you want your city handed to you on a plate?' An architect asked me this of Birmingham, meaning that while you had to work to get the best of the city, you may actually enjoy that adventure. 111 Places in Birmingham hands you a menu rather than recommending a dish. The selection is appetising, piquant, filling and occasionally exquisite. Other menus are available.