Vanessa Grasse ‘Movementscapes’, Juncture Dance Festival, Leeds

The walk is prefaced by a split stance / eyes closed exercise which allows us to become gently aware of our own body sense. Not easy on the cobbled slope: I sense a few people other than myself tipping or wobbling. Vanessa invites us to become aware of a space a metre – or just over a metre – above our heads. Specifics like this subtly suggest there’s a precision to her invisible art that we should take seriously.

I Was a Teenage Walking Artist – my visit to Walk On at Mac.

I’d rearrange found materials in situ, then vex my tutors by announcing that my work for the term was located beside a disused M&B pub six miles away. I was encouraged to instead photograph my sculptures or recreate them the studio. To my regret, I took their advice and it would be ten years or more before my efforts to guide people through these zones would naturally resurface.

Lost Rivers of Birmingham

I’ve long been aware of London’s well-known forgotten rivers and have walked their above ground routes. SW’s suggestion that this was possible in Birmingham was initially to tantalise people about their understanding of the city and what was possible. Eventually I realised that Birmingham did indeed have lost rivers…

Walk the Middle Way

There is a spirit of irony in choosing to walk the ring road: this route is all about the car and the marginalisation of everything else. Certainly that means the pedestrian but also the environment, the local economy and ultimately the city itself.

Car vs Pedestrian – review by James Kennedy

Here we were going to see hidden art, take in panoramic views, get some exercise, and observe the city around us. There would be exploration, and darkness and possible danger. The programme advised that this walk may not be suitable for those of a nervous disposition.

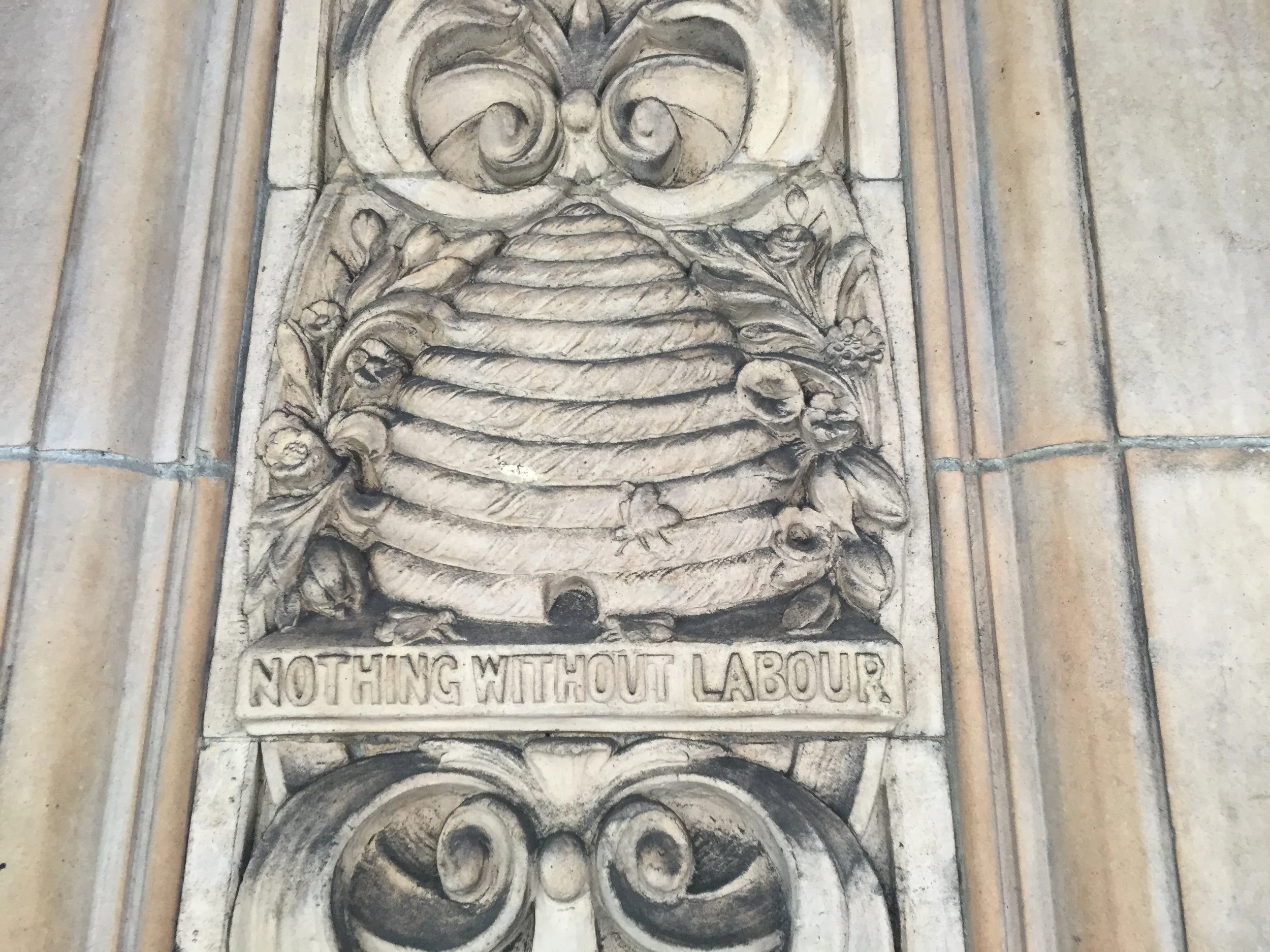

Words on Buildings // Laira Piccinato

Lettering on buildings used to indicate jobs for life, materiality on signage. Signs aren’t so much created to be part of architectural design anymore, more so than not they are designed to be disposed of when the business undergoes a re-branding, or the business goes out of business to be replaced by another business.

SOUNDkitchen // SOUNDwalk

Edgbaston reservoir lends itself well to a circular walk and to an opportunity to reflect on a natural environment at the edge of the city. It’s no coincidence that a Buddhist Monastery is located nearby.

Ladypool Road Through Time // Balsall Heath Local History Society

The longer you live in an area, the more questions you ask about it. That might be as simple is ‘where’s a good place to eat’, ‘is there a short cut to the bus stop?’ but eventually turns to ‘what exactly is that old octagonal turret opposite the Select N Save?’

Drag and Drop // David Helbich

‘Drag and Drop’: the drag part refers to you being guided while the drop part means that at some point on the walk, you will be dropped off to await collection by the next passing group. What this allows is a still, reflective moment in a context that rarely happens: standing still in an urban context.

Movementscapes // Vanessa Grasse

Vanessa Grasse is that rare fruit: the Sicilian that moves to Leeds. I know of only four.

Wait, Look, Drag, Drop

There was a moment of high drama when a slightly melancholic elderly gentleman, who I thought was doing nothing, turned out to be waiting. He was met after 35 mins by a granddaughter with hugs, a bouquet of flowers and a stack of chemistry textbooks. Instantly my understanding of the situation was thwarted. Only I witnessed that short story, and now you know it happened too.

Freeseeing and Night Photowalk: Two Events in the Fringe Festival

‘I created Free Seeing in response to the concept of ‘the found object’. Why not take it one step further and ‘find spaces’? We rarely take time to stop and really record what we see, so Free Seeing invites viewers to stop, look and really see….’

- Francis Lowe